El Universal

Jueves 28 de diciembre de 2006

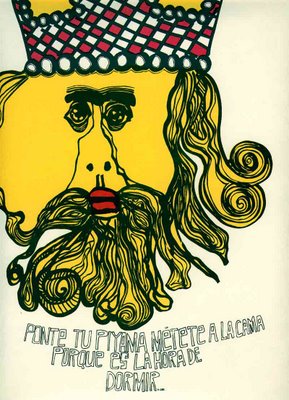

Residents serve "buñuelos" on the plates and later smash the china against a wall or the floor, and they make wishes for the next 12 months, which the majority of Oaxacans hope will be better than the past seven.

In May, unionized teachers launched a strike that left more than 1 million students without classes across Oaxaca.

The protests escalated in June when Gov. Ulises Ruiz tried to end the strike by force, a move that radicalized the teachers and led them to join with other grassroots groups.

Between June and November, at least 15 people - almost all of them Ruiz opponents - died in street clashes, dozens were injured and scores arrested, and the state sustained millions of dollars in damage and economic losses.

The buñuelos, which are made from wheat flour, milk and egg yolks, have a diameter of 30 centimeters (11.8 inches) and are sprinkled with sugar or drenched in syrup.

Buñuelos originated in the south of Spain and are yet another example of the Iberian Peninsula´s Arab heritage, Oaxacan historian Rubén Vasconcelos said.

Vasconcelos is an expert on the history and customs of the capital of Oaxaca, which is Mexico´s second-poorest state and also the jurisdiction with the largest indigenous population in terms both of absolute numbers and as a proportion of the total inhabitants.

Buñuelos are served for dessert on both Christmas Eve and New Year´s Eve, and until this year were sold by street vendors around the Oaxaca Cathedral in the Zócalo, or main square, of this picturesque colonial city.

Due to the camps set up by protesters in the square and clashes between activists and police in the surrounding area, tourism suffered this year.

Although arrests - mostly on trumped-up charges - were made of protest leaders in recent weeks, the Zócalo remained under tight security over Christmas, with police preventing protesters from entering.

SHIFT IN LOCALE

To maintain order, officials said, the buñuelos are being sold this year at an open-air market in the Plaza de la Danza, across from city hall and several blocks from the Zócalo.

The "sacrificed" plates are specially made in the potteries of Oaxaca, especially in Santa María Atzompa, where potters work with red clay.

"Before, the leading families of Oaxaca would break their china to welcome the new year with new utensils and throw out or toss the dishes," Miss Florinda, a vendor, told EFE about the tradition.

"You toss it and, when the plate is in the air, make a wish for when it shatters against the wall or floor, and your wish has been made and will come true," her fellow vendor, Sara Vasconcelos, said in front of a man-made wishing well used as a target for plates.

Oaxaca City´s tourism chief, Celestino Gómez, said the market was created to "unite the families of Oaxaca."

"This is an activity in which the city is taking part to present a range of foods and to jump-start the economy of the city and the state," Gómez said.

Enedino Reyes, a Oaxacan who visited the market with his family, was one of those wishing for better times.

"I have a small shoe shop and because of the problems here in the city recently, sales fell a lot, we don´t even have enough to pay the wages, or the rent. So I made a wish, to see what happens," Reyes said after eating a buñuelo and breaking a plate.

© 2006 Copyright El Universal-El Universal Online